Billy Pilgrim's Bunkmate

The professor seemed bursting with quirks: ramrod erect though middle-low in height, thinning hair, full suit, top rim glasses, a nasal yet precise voice, the epitome of a square to any clutch of students. He introduced himself to the  class—as he introduced himself in all of his classes—with the personal revelation of being a P.O.W. during World War 2. He explained further being billeted in a former meatpacking complex in Dresden, Germany called Schlachthaus fünf, or Slaughterhouse Five, made famous by fellow prisoner and novelist Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. So it goes.

class—as he introduced himself in all of his classes—with the personal revelation of being a P.O.W. during World War 2. He explained further being billeted in a former meatpacking complex in Dresden, Germany called Schlachthaus fünf, or Slaughterhouse Five, made famous by fellow prisoner and novelist Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. So it goes.

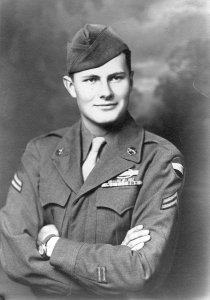

When I learned of Professor of History Gifford Doxsee’s death last summer at the age of 93, my mind meandered back to the single class I had taken under him at Ohio University in the late 1970s. The precise course title escapes me, but it explored the relationship between the Arab-Israeli conflict, OPEC and the then catchphrasey “Energy Crisis.” For those students who had attended high schools wearing heavy coats during the oil embargo after the Yom Kippur War, it was still very much a current event.

Both men, Doxsee and Vonnegut, were surviving soldiers of the 423rd regiment, 106th Infantry division, just-arrived green troops thinly deployed and overwhelmed by panzers and surrendered during the Battle of the Bulge. In interviews, Doxsee described December 19, 1944 as the darkest day of his life, although their commanding General sacrificed his career to save it, and those of his comrades.

Doxsee’s connection to the more famous man was not egocentric name-dropping, but rather an effort to impress upon his students a unique perspective: an up-close witness to the horrors of war, specifically the pointless firebombing of Dresden by Allied bombers on Valentine’s Day/Ash Wednesday of 1945. The disputed death tolls of 35,000 or 135,000 are frequent numbers, the latter more horrific than either of the atomic bombings later that year. Bureaucratic impetus doomed the heretofore-unscathed target, capital of Saxony, an ancient and elegant cultural center with no wartime industry. Churchill admitted that the attack was an act of terror, but later minimized the incident in his memoirs. Vonnegut sardonically acknowledged himself the only person alive ever to benefit from it, making $5 per victim on the novel.

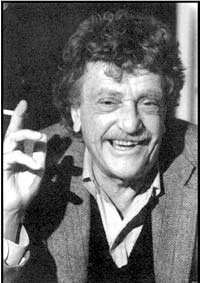

In the midst of the Vietnam conflict, Vonnegut’s critically acclaimed postmodern anti-war novel had catapulted him to pop-icon status, and remains the best known of 14 novels written before his death in 2007. Slaughterhouse Five ranks at 18 in Modern Library’s top 100 Books of the 20th Century. Zealous local school boards in the United States single-out the novel for obscenity and The Vonnegut Center in Indianapolis offers free books to affected students. A film adaptation released in 1972, Vonnegut called “flawless,” although his cameo in the film cut out. In Back To School, he ghost-wrote a book report on himself for Rodney Dangerfield’s character. “Whoever did write this doesn't know the first thing about Kurt Vonnegut!”

In the midst of the Vietnam conflict, Vonnegut’s critically acclaimed postmodern anti-war novel had catapulted him to pop-icon status, and remains the best known of 14 novels written before his death in 2007. Slaughterhouse Five ranks at 18 in Modern Library’s top 100 Books of the 20th Century. Zealous local school boards in the United States single-out the novel for obscenity and The Vonnegut Center in Indianapolis offers free books to affected students. A film adaptation released in 1972, Vonnegut called “flawless,” although his cameo in the film cut out. In Back To School, he ghost-wrote a book report on himself for Rodney Dangerfield’s character. “Whoever did write this doesn't know the first thing about Kurt Vonnegut!”

At some impromptu bull session in the following weeks, Slaughterhouse would come up again. The professor was candid and relaxed about his wartime experiences. He escaped death several times, once when the RAF bombed their prison train, and another time during the final days of the war as they marched to the American lines and were strafed by Russian warplanes. The main event, however, was the eight hours huddled underground as 800 RAF Lancasters firebombed the city above.

The Americans were detailed then to clearing the rubble and mining the bodies of the dead. The SS used flamethrowers to light the stacked corpses. The starving POWs fed from canned goods in the cellars where they gathered charred victims, their middle-aged guards looking the other way, provided they did not carry anything out. A Hitler Youth guard nicknamed “Junior” was Vonnegut’s nemesis, taunting and poking him continually with a bayonet in an attempt to provoke him. Doxsee recalled Vonnegut’s self-control.

One unsubtle, flippant inquiry: Which character were you? It was not so difficult to imagine this middle-aged square peg’s resemblance to the unstuck-in-time optometrist Billy Pilgrim himself, perhaps bound for a rendezvous with Montana Wildhack on Tralfamadore. We were all Billy Pilgrim, or at the very least his bunkmates. Doxsee reminiscences are prominent in an anthology of Slaughterhouse alumni, a dark nostalgia of haunted Pilgrims. So it goes.

Vonnegut revealed years later that the time-traveling and pacifist protagonist Billy Pilgrim—an Episcopal army chaplain’s assistant in the Slaughterhouse and future optometrist—was based in part on fellow prisoner Edward Reginald Crone Jr., a classmate and friend of Doxsee’s at Hobart College prior to their enlistment. He was one of three in the group of about 100 POWs who died during captivity. The Edgar Derby character would be executed for stealing a teapot, but his real life counterpart was discovered with a jar of beans under his coat.

Vonnegut revealed years later that the time-traveling and pacifist protagonist Billy Pilgrim—an Episcopal army chaplain’s assistant in the Slaughterhouse and future optometrist—was based in part on fellow prisoner Edward Reginald Crone Jr., a classmate and friend of Doxsee’s at Hobart College prior to their enlistment. He was one of three in the group of about 100 POWs who died during captivity. The Edgar Derby character would be executed for stealing a teapot, but his real life counterpart was discovered with a jar of beans under his coat.

The physical description of Pilgrim, however, at 6’3” and 140 lbs., resembled Vonnegut himself. Doxsee remembered the author to be the tallest and most conspicuous of their small group of prisoners assigned to a work detail at a nearby Malt Factory before the bombing. The starving Americans surreptitiously gulped spoonfuls of malt syrup while working. In the book, Billy Pilgrim passes a spoon of it to his doomed friend Edgar Derby, who bursts into tears.

Doxsee was surprised to learn that his fellow classmate was identified by Vonnegut as the basis of Pilgrim, who he had always thought starved to death trading the scant rations for tobacco. He learned later from another former prisoner that Crone, who aspired to the Episcopal ministry, did not smoke, but often shared his portions with his more desperate fellow prisoners. After the war, Doxsee attended Cornell (as did Vonnegut, prior to it), and then Harvard, where he eventually received his Ph.D. His specialty was Middle Eastern and African history, concentrating on the impact of colonialism.

In context of our classroom subject, Doxsee recounted while being marched to the rear, the German army, rumbled to the front with their equipment entirely under horsepower. One of the objectives of the Ardennes counter-offensive was a fuel depot at the port of Antwerp. He claimed that the Allied victory was narrower than now appreciated, the bombing of cities had small effect, and the lack of fuel was everything. Our “energy crisis” class concluded that with our dependence on foreign oil at an all-time high, the discovery of large reserves necessary to feed the binge was perilously unlikely. Climate change had yet to enter our lexicon.

In context of our classroom subject, Doxsee recounted while being marched to the rear, the German army, rumbled to the front with their equipment entirely under horsepower. One of the objectives of the Ardennes counter-offensive was a fuel depot at the port of Antwerp. He claimed that the Allied victory was narrower than now appreciated, the bombing of cities had small effect, and the lack of fuel was everything. Our “energy crisis” class concluded that with our dependence on foreign oil at an all-time high, the discovery of large reserves necessary to feed the binge was perilously unlikely. Climate change had yet to enter our lexicon.

Most of what I have learned about Doxsee was after last seeing him, amongst a group of professors attending an anti-draft rally on campus in 1980. After Vonnegut’s death in 2007, by tripping over a dog leash down the steps of his New York City brownstone, the professor was sought out for reaction. He was a haunted soul. His children said as much. Vonnegut was a child of an inexplicable suicide, that of his mother while he was home on a weekend pass, and just months before he shipped out to the western front and captivity. He once wrote his wife of an early premonition, an unspecific death by dog.

Doxsee was deeply religious, crediting his mother’s prayers to surviving the war and imprisonment.. He retired from the university in 1994. For twenty years he cared for his Alzheimer's-stricken wife, and was involved in worthy community causes, a national POW organization, teaching at a nearby prison, and various church activities, until death. On request, always happy to address English literature classrooms assigned the novel. He last spoke to the author in 1997 after a lecture at Ohio Wesleyan University.

Both men had revisited Dresden after the war, Vonnegut partly dedicated Slaughterhouse to a cab driver in the city, which he said resembled Dayton, Ohio in its staid, communist glory. Today, Neo-Nazi groups in Germany preserve the anniversary with angry marches. The Schlachthaus Fünf complex has been converted into a trendy convention and event center, with the original architecture mostly intact. The basement where the POWs huddled during the eight hours of bombardment includes a small memorial to Kurt Vonnegut and his novel. So it goes.

Comments