A black and white Polaroid taken by my grandfather commemorates one of several pilgrimages we took by bus back to his birthplace in north-central Georgia. The scattered village where he was born is a remnant of what was once the family plantation. The sound of U.S 441 rumbles nearby.

This was over fifty years ago, and memory is an imperfect monochrome. I was an annoying child eager to ham for the noisy, black-bellowed Model 95 Land Camera, a contraption as sophisticated to me as a Gemini orbiter, and as ever present as his pipe and fedora.

“Now, then…,” he would repeat, applying the gum stick to several prints, ostensibly to prevent their fading too quickly. The chemical stench of the gum was as familiar as the aroma of his preferred Prince Albert tobacco.

He was quite elderly when I was small and I was his only grandchild, something he would remind me of when I became a morose teenager. He also reminded me that he had never known his own grandfather because his had died in the Civil War. What is distant history to most has always been to me something closer in proximity.

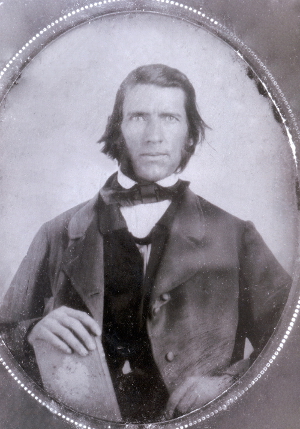

Perhaps my obsession with history originated from the infrequent talk of this martyred Confederate Corporal, a reluctant ghost. A copy of a pre-war Ambrotype, which hung for years in grandfather’s living room, shows a confident, handsome fellow. Died at the Battle of the Wilderness, was erroneously repeated.

My Grandfather had the unusual middle name Napoleon. He said he had no idea how it came to be. I discovered years later that his grandmother, the Corporal’s widow, had a brother with the same name. Something inexplicably never discussed, like the absent Corporal, the central tragedy of their lives.

One vivid recollection has had a lasting impact: At a country store, an unpainted shack bedecked with coca-cola signage and festooned with yellow fly strips, grandfather and I encountered one of his childhood companions. When introduced—I had yet to meet a black person in my life—the old fellow leaned into me and demanded to know my last name. When I told him, he exclaimed, “Well that’s my last name too! Do you think we might be related?” The adults present had a good chuckle, but it would be some time before I understood the darkness of their humor.

The Patriarch, the Corporal’s own grandfather, had been an adolescent militiaman in the Revolution. He lived nine decades and accumulated twenty square miles of cotton fields and piney woods. As a state assemblyman and senator, he played a role in dispossessing the Cherokee of the Dahlonega gold fields, and his eldest lawyer son acquired and managed a mine for the benefit of the whole clan. The plantation property was mostly tenanted. The number of slaves in the record is fewer than one might expect.

A family history typically portrayed the old man as a benevolent master, his tolerance of the peculiar institution both sanctioned and forgiven by pious Calvinism. His will allowed his slaves to live with any of his children or grandchildren they preferred. Two sisters were to remain together permanently. The men permitted to visit their wives once a week. These instructions were enforceable by punishment of “forfeiture” he proclaimed, to what entity other than manumission he failed to disclose.

The Corporal and his brothers, all of whom survived the war, were by no means raised as pampered aristocrats, all having learned separate trades. His was with the hammer and anvil. He married late, courting the daughter of a tailor in Augusta. His only child was an infant when he abandoned them for the army. The wife never remarried, receiving a widow’s pension well into the 20th Century.

If abandonment is too strong a term, being a member of the militia was required by law. This was true prior to the Revolution as it is required unofficially even today. Its primary mission then was to organize slave patrols. The militias also mustered regularly for social events, summer picnics and political speeches, parading for the admiration of eligible ladies in garish homespun uniforms. When the drums of war became deafening the militias eagerly morphed into combat companies, and those same admiring ladies encouraged them onward with appalling enthusiasm.

For a time I lived vicariously in the combat prowess of his regiment, the 18th Georgia Infantry, famously brigaded with three from Texas under General Hood. That first winter at Dumfries, Virginia, they died in large numbers of childhood diseases, mumps and measles. The brigade then fought gallantly at Gaines’s Mills, and then at Second Manassas, where they spearheaded Longstreet’s assault on Pope’s left, scattering the Yankees in retreat. They captured two stands of colors and a battery of cannon, decimating the 5th New York Zouaves so completely its survivors served out the remainder of the war as reservists and hospital orderlies.

I have since doubted his direct involvement in combat. He was forty years old, officially designated in the muster rolls as regimental blacksmith. I imagine him instead bringing up the rear, a wagon driver hauling supplies and smithy tools. The injury that killed him—dropping a hot horseshoe into his boot, in an army nearly bereft of shoes—confirms for me this conjecture. The accident happened at camp after the retreat from Antietam. He lingered for several days at a hospital in Richmond and died of tetanus.

As the conflict drew down, the Corporal’s widowed aunt, rumored to have squandered a small fortune in useless Confederate bonds, resisted reconstruction even in death. Early in 1865, with the neighborhood occupied by Yankees, she solemnly made out her last will and testament, disposing of all property she still possessed, including a handful of slaves she technically no longer owned. A finer point to her grief and oblivious fanaticism, she willed a “Negro boy named Jefferson” to her nephew the Corporal, already known to have been dead three years.

Grandfather liked to repeat the story how his orphaned father, at the age of six, was detained for throwing rocks at the Yankees as they marched through the village. The intervention of his black “Mammy” rescued him from the angry officers.

My interest in family history and the Civil War has waned over time as new interests preoccupied. I once stumbled upon a reenactment camp, fascinated by the costumes and the detail of their accoutrements. A friendly re-enactor invited me to join the Sons of Confederate Veterans, an organization dedicated to honoring and preserving the heritage of this defeated army. The conversation devolved into the same Lost Cause apologia and equivocations I had already adequately studied; The South had a right to secede. The war was not about slavery. The business card he proffered I tossed into a desk drawer and forgot.

Devotion to tradition and heritage is noteworthy, but slavery is vile and treason dishonorable. It doesn’t seem we will ever arrive at a neutral place where the symbols of this struggle can quietly coexist with the lingering, abhorrent reality of it. The fate of battle flags and statues will become what they need to become someday: fading and tumbling into irrelevancy and rubble.

The Corporal’s monument in Oakwood Cemetery in Richmond, unlike the mass-produced effigies of the men who lead him and his comrades to slaughter, is a square numbered block shared with two other men. I had once acquired, but long since misplaced, the number of his unvisited grave. This has always been the ultimate Confederate monument, and for me a personal and private memorial.

Fifty years ago, Grandfather and I struggled up into the woods behind the old place. He showed me a grand old tree with a knot half way up the trunk, a knot he had tied into it as a boy when it was still a sapling. It was an awesome curiosity. If there existed an old Polaroid print of it, it would be a dull thing by now. But somehow I know even without it, that there is no possible way that that tree still stands.

Comments